Working for good looks

Making their customers prettier is the everyday life of hair dressers and make-up artists.

Since 2016, the share of employees able to make ends meet has been increasing. Nonetheless, 46 percent say that their wages or salaries are just barely - or not at all - enough to live on.

In the past three years, the number of employees who are barely or not able to live on their incomes has decreased perceptibly. While the share was 55 percent in 2015, it was “only” 46 percent on average in the years 2017 and 2018.

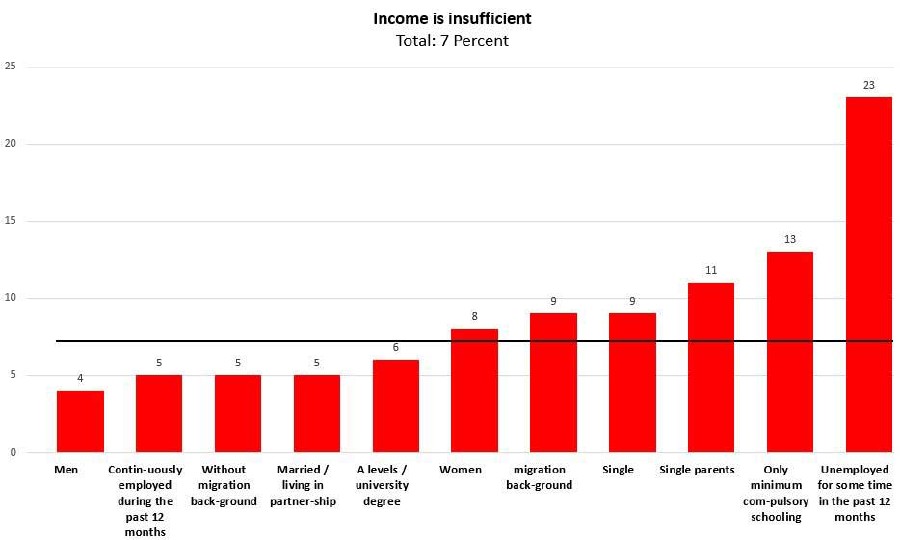

This gratifying development, however, cannot belie the fact that almost half of the employees still have difficulty covering their cost of living with what they earn - especially women and employees with only minimum compulsory schooling. Where women are concerned, the main reason for this is the high share of part-time work, whereas with people of low education it is the fact that they often only get jobs in poorly paid sectors.

A share of currently six percent (approx. 220,000 people) - which has remained relatively stable over the years - say that they are not paid enough to make ends meet. Conspicuously, many formerly unemployed people are affected by this aspect: currently, 23 percent of those who were out of work once in the past twelve months hold jobs that do not earn them enough to make a living. Their median income is 300 euros lower than that of employees who were working continuously during the past twelve months.

41 percent of the formerly unemployed now work in part-time jobs, 15 percent in marginal employments. One quarter have a fixed-term work contract, ten percent work as temporary workers. This shows that for a majority of the unemployed a way back into the labour market is only via precarious employments.

“Employment is considered precarious when employees can hardly or not at all live on their incomes, when the employment is not intended to be permanent, or when people work part-time involuntarily. This includes contract and temporary work, employment in the low-wage sector, involuntary part-time work, mini-jobs, or funded work opportunities.”

This definition of the German DGB union applies to seven percent of the employees in Austria. Their Work Climate Index is only 85 points - hence 26 points below that of regular employees. People in precarious employments are most dissatisfied with their career opportunities, their options for participation at work, their relationships with colleagues, and their own social standings.

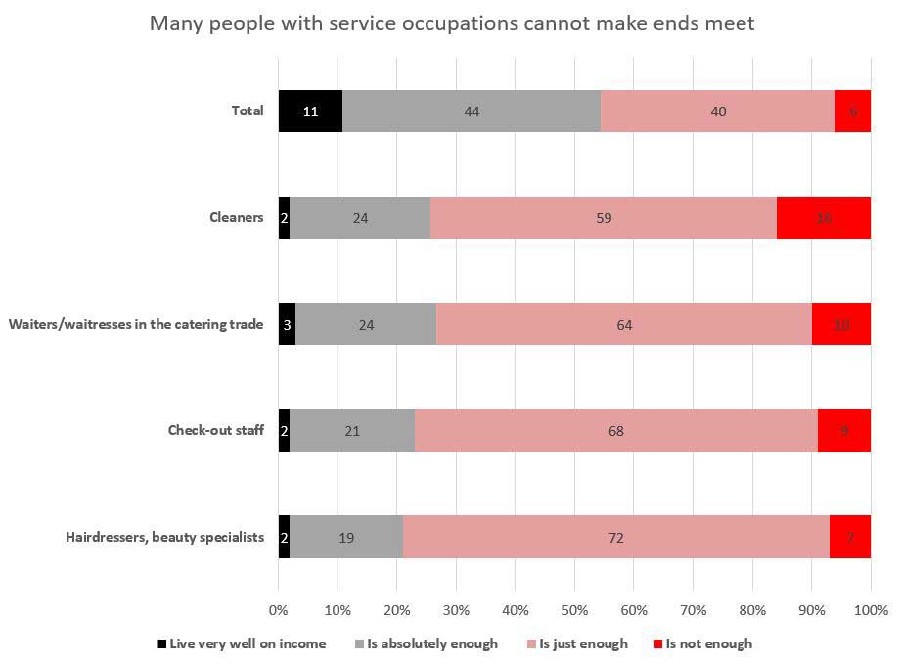

In some sectors, the majority of the employees can just barely or not at all live on their incomes - for example in the cleaning and the catering trade.

The risks of finding only precarious employment is unequally distributed among sector and professions. In the catering trade, for example, approx. ten percent of the employees hold precarious jobs, compared to 18 percent in the textile sector, or 24 percent in other economic services. Moreover, almost one quarter of the job starters who have completed vocational training and education find themselves in precarious employment situations.

16 percent of the cleaners say that they are not paid enough to live on, another 59 percent say that they just get by. This means that a total of three quarters of the cleaners have difficulty living on their income. The share is similarly high among the waiters/waitresses in the catering trade (74 percent), among the check-out staff (77 percent), and among those rendering personal services such as hairdressers and beauty specialists (79 percent). Making ends meet is easiest for school teachers: 85 of them say that they can live well on what they earn and/or it is absolutely sufficient.

Satisfaction with life is 18 percentage points lower among people who cannot live on their income than among those who can. 57 percent are dissatisfied with their social positions in society. And what is particularly dramatic: 84 percent do not believe that they will be able to live on their pensions later on. Among those who earn enough, this share is only 13 percent.

According to the French sociologist Robert Castel, precarity is the new social issue of the 21st century. He talks about a “recurrence of social insecurity” in modern societies. And in actual fact, many employments have become more and more precarious in terms of income, job security, stability and predictability. Although the number of people who are barely able to make ends meet is declining due to tax reform, minimum pay and good wage agreements, almost half of the employees do not earn enough to make a living. Both the wage ratio and the mean real earnings are on the decrease.

Employees are the real performers in our country - without them everything would grind to a halt, either in companies, in associations, in blue-light organizations, or in childcare and elderly care. These services have to be honoured adequately. Therefore, it is high time for a major pay rise - also as a compensation for the twelve-hour day. Because the work performed by the employees is worth so much more!

Almost one quarter of the employees in Austria have a migration background. They are more dissatisfied, more stressed, and often discriminated.

Migrants often work in jobs for which they are overqualified. According to “Statistics Austria”, about 866,000 people with a migration background were gainfully employed in 2017. This is a share of 23 percent. The majority of them were still born abroad themselves. Almost four out of ten have their roots in another EU or EFTA country, some 30 percent come from successor states to former Yugoslavia, and 14 percent from Turkey.

Migrants are clearly more dissatisfied - regardless of their age, education or the region where they live. Their Work Climate Index is 102 index points, which means that, over the years, it has remained eight to ten index points below that of employees with Austrian roots. One possible explanation might be the fact that migrant employees are discriminated in the labour market and therefore often work in jobs for which they are overqualified. More than one fifth of all migrants who have completed an apprenticeship work as unskilled employees - compared to “only” eight percent of the Austrians.

Unsurprisingly, migrants are therefore more dissatisfied with their jobs, working hours, incomes, and most of all with the opportunities for promotion and development. At the same time, they suffer from higher physical and psychological stress. However, migrants are more optimistic: 78 percent of them think that the Austrian economy will develop positively. Only 67 percent of the employees of Austrian origin think so.

In the economic and socio-political discussions far too little attention is paid to the employees' view. This may also be due to the fact that, allegedly, insufficient solid data are available. For 21 years, the Austrian Work Climate Index has been supplying these data, and it has thus become a benchmark for economic and social change from the employees' point of view. It examines their assessments with respect to society, company, work and expectations. The Work Climate Index captures the subjective dimension, thus expanding the knowledge of economic developments and their implications for society.

The calculation of the Work Climate Index is based on quarterly surveys taken among Austrian employees. The random sample of approx. 4000 respondents each year is representative so as to enable telling conclusions regarding the mental state of all employees. Since the spring of 1997, the Work Climate Index has been calculated and published twice a year. There are also supplementary special evaluations.

For current results and background information please refer to ooe.arbeiterkammer.at/arbeitsklima. There you will not only find the comprehensive work climate database for evaluation, but you can also calculate your personal satisfaction index with your workplace online within just a few minutes. You will also find the Executive Monitor Report online, which deals with the question of how satisfied Austrian executives are with their work.

Many craftspeople are dissatisfied with their work, mainly because of high physical stress.

To be able to analyse the job satisfaction of craftspeople, the professions construction worker, bricklayer, carpenter, cabinetmaker, joiner, roofer, and painter have been rolled into one group. 90 percent of this group are male, six out of ten have completed an apprenticeship, and the majority are skilled workers in construction or industry.

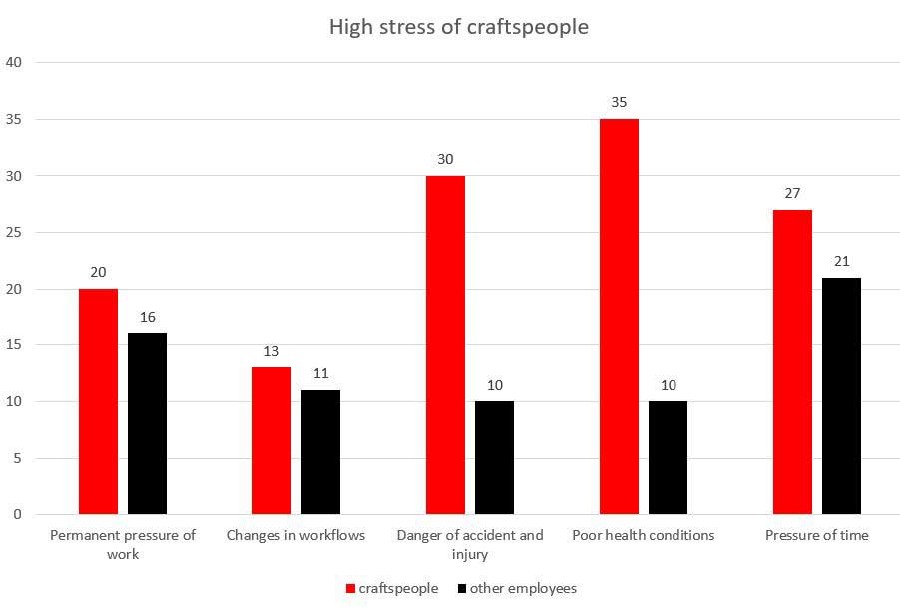

Taking the average of the years 2015 to 2018, job satisfaction in these occupational groups was eight index points lower than among the other employees. The main reason for this is the higher physical stress. More than one third suffer from poor health conditions, and three out of ten complain about the high risk of accident and injury, which is about three times as many as in other occupational groups.

More than one quarter of the craftspeople are stressed by general time pressure, one fifth by a continuous pressure of work. Eight out of ten work overtime at least sometimes, 27 percent even frequently, compared to “only” 17 percent on average across all sectors. This means that craftspeople work 42 hours a week. Six out of ten do not think they will be able to do their jobs until retirement.

The new General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) required us to ask all subscribers of our Work Climate Index Newsletter if and in which form they wished to continue to receive the newsletter. In the course of this survey we also created the opportunity to get the newsletter by e-mail. This is quite simple: Go to ooe.arbeiterkammer.at/Newsletter.html, select the newsletter “Work Climate Index” and enter your data. Within a few seconds you will get an e-mail asking you to confirm your ordering the newsletter. If you want to get the printed version of the newsletter and have not yet told us so, just send an e-mail with your name, postal address, and your consent to our sending it to marketing@akooe.at.

© 2026 AK Oberösterreich |

Volksgartenstrasse 40 4020 Linz, +43 50 6906 0