Dieses Bild teilen über:

Almost every third employee in Austria knows cases of burnout in his/her company, and almost one third consider themselves to be at least slightly susceptible to burnout.

For nearly one third of the employees the burden at work is too high. This applies particularly to people with only minimum compulsory schooling: In this group almost half of the employees say that they suffer from an excessive workload. Of course, this increases frustration at work as well as the danger of burning out in the job.

As yet, “only” six percent of employees have been on sick leave because of a burnout syndrome. In this case, too, people with only compulsory schooling stand out in a negative sense: The share is twice as high among this group. The gender ratio, however, is balanced: To date, seven percent of the men and six percent of the women have been on sick leave because of a burnout syndrome.

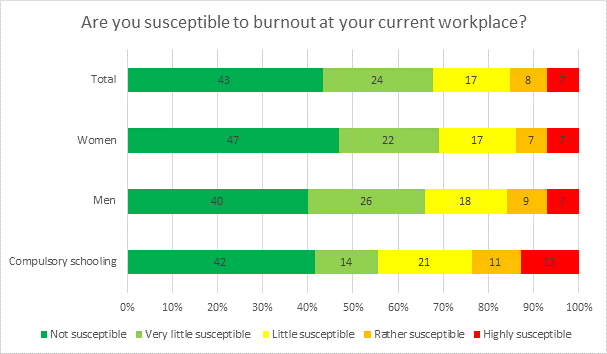

The problem becomes more tangible when we take a look at the subjective estimation of people’s risk to develop a burnout: One third of the Austrian employees consider themselves to be at least slightly susceptible to burnout in their present jobs. In this case, too, it is conspicuous that the threat people feel on a subjective level is clearly higher among people with only minimum compulsory schooling.

People also have long since started to realize the high workload in their companies. Almost four out of ten employees worry about their colleagues. And nearly one third say that they know someone in their companies who has already been away on sick leave because of a burnout syndrome.

In the companies, for six out of ten employees, burnout has not yet become an issue. Vice versa, however, this means that the subject is quite topical for the other four in ten people - and more commonly between colleagues than among executives: While employees talk about burnout in 38 percent of the companies, only 19 percent of the companies’ managements consider this medical condition to be an issue.

But if a person actually falls ill, people in his/her professional environment respond sympathetically: Three quarters think that their colleagues will show sympathy if someone suffers from a burnout. Six out of ten people who actually suffered from a burnout themselves expect such understanding from their colleagues. And three quarters of these employees think that executives deal sympathetically with this medical condition. Across the total of respondents this value is 69 percent.

Comment by Dr. JOHANN KALLIAUER, President of the Upper Austrian Chamber of Labour

For many employees it is increasingly difficult to reconcile the growing demands in the job with the need for a fulfilled private and family life while simultaneously meeting their own high standards regarding the quality of their work. Everything seems important. But sometimes it is simply too much. This fact is corroborated by the rising number of employees who are burnt out and at the end of their tether. Therefore, stress prevention in companies is becoming more and more important.

This is why we expect an increased commitment of employers both in the field of prevention and in terms of re-entry after recovery. The new law regarding re-integration entering into force as from 1 July will make it possible for employees to start again gently. As regards burnout prevention, it will not do to just survey the mental burden at the workplace. Employers have to take the results of such evaluation seriously and implement effective measures against conditions at work that make people ill. Because one thing is for sure: Work must not make people ill!

For current results and background information please refer to ooe.arbeiterkammer.at/arbeitsklima. There you will not only find the comprehensive work climate database for evaluation, but it is also possible to calculate your personal satisfaction index with your workplace online within just a few minutes.

Fewer employees than before consider their work as physically or mentally straining. However, stress remains to be a common phenomenon.

In the past twenty years the number of employees not suffering from any physical or mental burden has grown considerably. While, in 1997, 17 percent of the people felt no time pressure at all, this share has grown to 38 percent in 2017. Over the same time period the percentage of people whose work is not emotionally disturbing and exhausting has risen from 30 to 60 percent. And the number of people who do not feel stressed at all by technical changes or varying workflows has grown by ten percent today.

This positive long-term trend, however, should not hide the truth that stress at work is a common phenomenon and in many cases also a problem. The fact that fewer and fewer employees feel mentally strained at work also shows that stress limits have shifted and stress has become an ordinary element of everyday working life.

Employees feel stressed, among other things, by their work duties per se, by the conditions at work, pressure of time, and pressure of work. Almost one quarter of the employees feel burdened by pressure of time, approximately one sixth by a constant pressure of work. Men feel a little more often burdened by both forms of stress than women. Unskilled workers feel most burdened by pressure of time and pressure of work.

One tenth of all employees, each, find technical or organizational changes as well as varying workflows stressful. If we consider stress of time and organizational stress together, some occupational groups stand out for a particularly high burden: female textile workers, nursing staff, and construction workers.

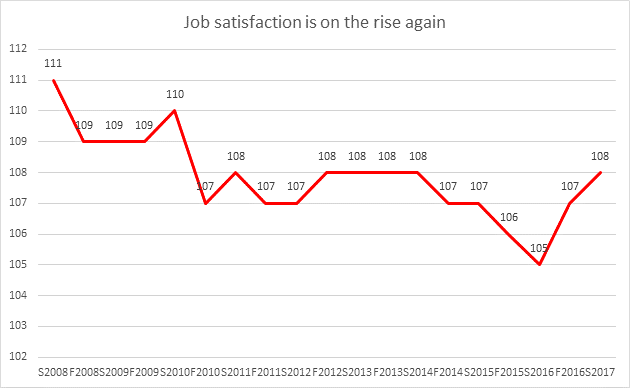

One year ago, job satisfaction was at a historical low. Now employees look ahead more optimistically.

One year ago, the Work Climate Index had reached a historical low of 105 points. At that time, employees were pessimistic regarding the economic development and their chances in the labour market, at the same time dissatisfaction with the environment at the workplace and central aspects of work were on the rise.

One year later, the Work Climate Index has recovered, being 108 points at present. Considering the data in detail, it is conspicuous that almost all aspects of job satisfaction have improved, mainly the employees’ estimation in terms of the economic future of the country and the companies, optimism with regard to career and promotion prospects, as well as satisfaction with superiors. Satisfaction with company benefits and income has also seen a significant increase.

The index has risen in almost all occupational groups. Previously, people with only minimum compulsory schooling showed an alarmingly low level of job satisfaction. But within one year, they too have stepped up three points. With just under 100 index points, however, their job satisfaction is still clearly lower than that of all other education groups. In case of academics, things are also looking up. This group was one of those whose job satisfaction had traditionally been high but whose optimism had declined markedly of late. With a plus of five index points since the spring of 2016 employees with a university diploma have again become the most satisfied group in the employment market. Even young people under 26 years of age are more satisfied than one year ago.

In the economic and socio-political discussions far too little attention is paid to the employees' view. This may also be due to the fact that, allegedly, insufficient solid data are available. For almost 20 years, the Austrian Work Climate Index has been supplying these data, and it has thus become a benchmark for economic and social change from the employees' point of view. It examines their assessments with respect to society, company, work and expectations. The Work Climate Index captures the subjective dimension, thus expanding the knowledge of economic developments and their implications for society.

The calculation of the Work Climate Index is based on quarterly surveys taken among Austrian employees. The random sample of approx. 4000 respondents each year is representative so as to enable telling conclusions regarding the mental state of all employees. Since the spring of 1997, the Work Climate Index has been calculated and published twice a year. There are also supplementary special evaluations.

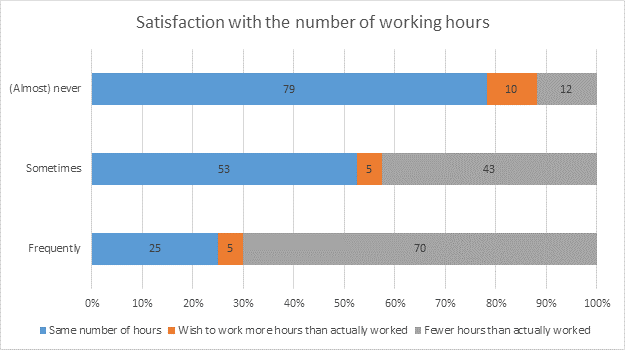

More and more employees are faced with flexible working time regulations that do not address their needs. Until 2007, satisfaction with working time regulations was higher than 80 percent. Since then it has fallen to 73 percent. This means that more than one quarter of the employees in Austria are moderately satisfied, little satisfied or not satisfied at all with working time regulations.

Satisfaction with working time regulations depends largely on the private environment and is closely tied to the way they allow a good balance of job and private life. 91 percent of the employees who are satisfied with their working time regulations find it easy to reconcile their jobs and private lives, whereas among those who are not satisfied with their working time regulations only half of the employees have a good work-life balance.

This balance between the job and private life is also adversely affected when working hours are controlled by others: While only two thirds of the employees with irregular working hours consider their work-life balance as good, 84 percent of the respondents with fixed working hours say that they are well able to balance their jobs and private lives.

© 2026 AK Oberösterreich |

Volksgartenstrasse 40 4020 Linz, +43 50 6906 0